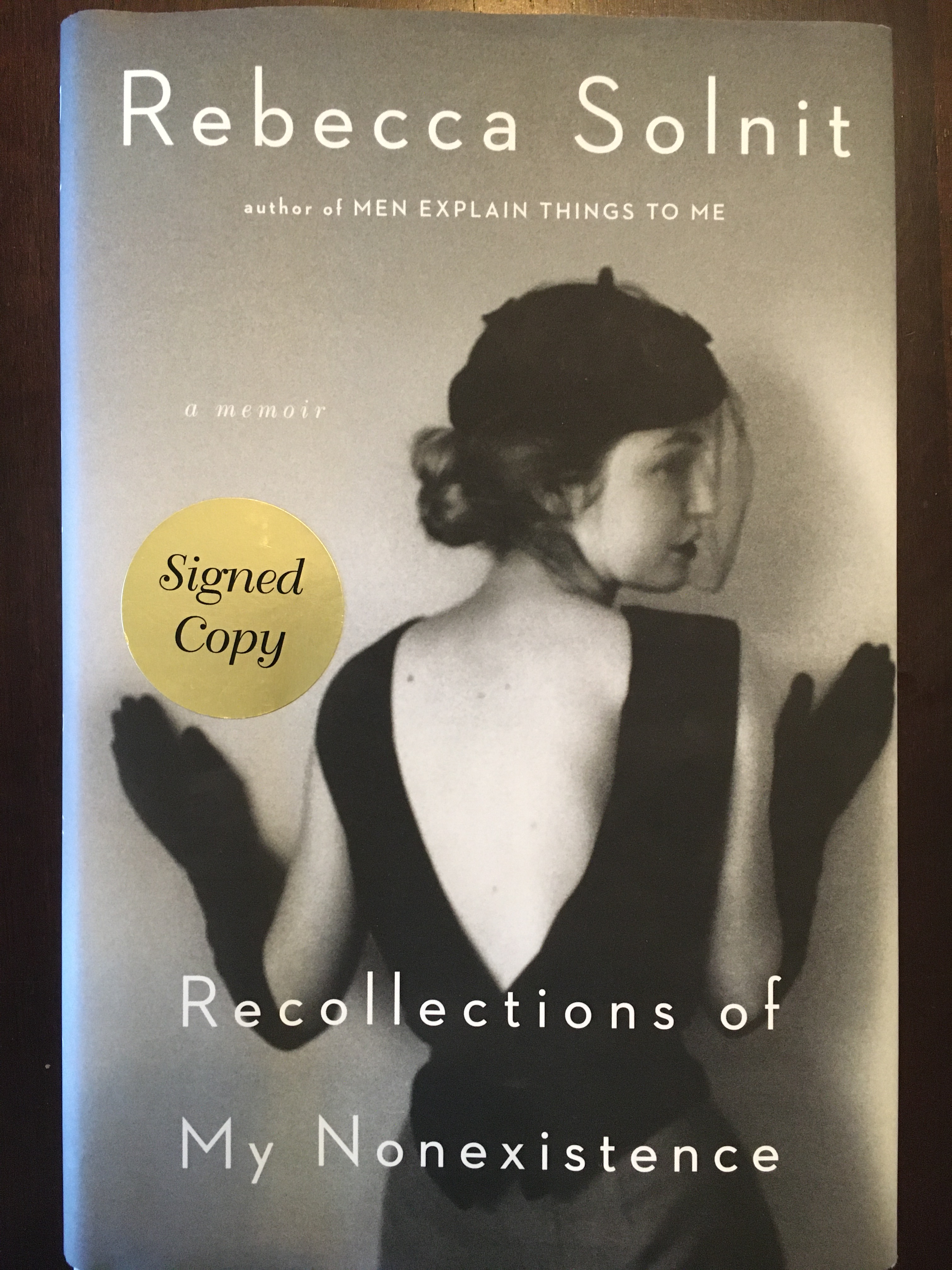

Rebecca Solnit’s new memoir Recollections of My Nonexistence resembles her many essay collections that came before it: provocative yet relatively opaque. She weaves ideas together, creates surprising connections, and guides readers to see their experiences in new ways (a la “Men Explain Things to Me”) — but she does not delve into personal details. Unlike other contemporary memoirists, she writes towards commonality. Through brief vignettes that begin with her own experiences as a young woman, she reveals the conditional of all young woman. She makes us visible to ourselves.

As a reader and 26-year-old woman, I found this book hard to read — but not for the usual reasons. Solnit pushes right up to the edge of Emily Dickinson’s advice that “the truth must dazzle gradually.” Many of her conclusions felt like looking into direct sunlight. In a way, I need to write this review to process that initial sting.

Though her memoir collection also includes essays writes about growing up in San Francisco, studying the southwestern U.S., and becoming a writer, Solnit’s most powerful chapters meditate on feminism, i.e. growing up female. She uses the titular word “nonexistence” because “in my case, it wasn’t a silencing. . . no speech was stopped; it never started, or it had been stopped so far back I don’t remember how it happened.” Her goal, she states, is encouragement: “a word that, though it carries the stigma of niceness, literally means to instill courage.” To do so, she begins by examining how courage is ripped away from young women. She then discusses how they might go about getting it back.

Solnit’s careful recounting of her past nonexistence (in “silent fury”) shed new light on my own. I’ll explore a few such instances here.

“I became an expert at fading and slipping and sneaking away, backing off, squirming out of tight situations, dodging unwanted hugs and kisses and hands, at taking up less and less space on the bus as yet another man spread into my seat, at gradually disengaging, or suddenly absenting myself.”

“Life During Wartime”

For me, passages such as these yank to the surface a decade-long pattern of suffering under patriarchy, but not understanding what was happening to me, or knowing what to call it. Solnit’s words brought up so many memories; memories that make me sweaty and nervous; memories that make me sad about the state of the world; memories that, despite my efforts to bury them, inform the way I move through the world.

“Dodging unwanted hugs and kisses,” takes me back to my first job out of college as an executive assistant to a 69-year-old lawyer, a founding partner at a Chicago law firm and real estate attorney for one of the world’s richest men. He would ask me to dinner with business partners, take me out for drinks in the afternoon (“You’ve never had mezcal? I’m ordering it for you”), put his arm around me, ask me why I wasn’t having fun, try to kiss me in greeting (he got the cheek), tell me I was attractive, and make sex jokes to his coworkers, knowing part of my job was to listen to all of his phone calls and read all of his emails.

In response to this treatment, I, to my own frustration, did nothing but comply and evade. “Okay I’ll drink that,” “yeah I’m fine,” “haha,” “okay,” just get through the day and get out. I vented to my friends, where it was safe, but never to him. As Solnit describes, evasiveness stems from a fear of escalation. Escalation leads to violence. She writes, “Men would make proposals, demands, endeavor to strike up conversations and the endeavors quickly turned to fury. I knew of no way to say No, I’m not interested, that would not be inflammatory, and so there was nothing to say. They was no work words could do for me, and so I had no words.”

Eventually, I gave my boss what it seemed he wanted: I vanished. I packed my things and called him to let him know that I was quitting. To him, it was a shock; to me, it was the natural conclusion of his year-long effort to annihilate my personhood. That was in August 2017. When the Harvey Weinstein story broke two months later, I believed for the first time that I had done the right thing. (And considered that maybe I should’ve gone to HR, or Ronan Farrow – but that’s another story.)

“I erased myself as much as possible, because to be was to be a target.”

“Life During Wartime”

Maybe it started earlier than a decade ago. As a 10-year-old in Boise, Idaho, I took a Hunter’s Safety class with my dad, my friend Austyn, and her dad. Austyn’s dad was an avid hunter who wanted to take us duck hunting with him that season. I was game for anything – I just wanted to hang out with my buddy, even if the activity did not particularly appeal to me. The rest of the class was full of other young boys and their dads. One evening, as I remember it, the teacher called on me to answer what turned out to be a trick question. My hand had not been raised. He said, “You there.” I snapped to attention, the blood rushing to my face. “What’s the difference between bending the law and breaking the law?” I quietly began to stumble through some explanation of how the two might be different, but the teacher interrupted. “Wrong, he said, “there’s no difference.” Then another kid’s dad shouted: “Women, am I right?!” and the whole room cracked up.

I took away a feeling that it was dangerous to speak; that I lacked knowledge because of my gender; and that men only listened to me insofar as it gave them an opportunity to appear superior, or to make other men laugh.

“Thinness is a literal armor against being reproached for being soft, a word that means both yielding, cushiony flesh and the moral weakness that comes from being undisciplined. And from consuming food and taking up space.”

“Disappearing Acts”

Around 16-years-old, when my body started shape-shifting, I was horrified to be losing the one thing I had long been praised for — being skinny. When I tried to regain control of my body, I tripped some internal brain wiring and fell into the obsessive hamster wheel of an eating disorder. I went from 120 ish pounds to 96, eating with rigidity and running every day. I stopped caring about boys, about friends, about what people thought of me – which in a dissociative way, felt like freedom. But as my condition deteriorated, I realized it was a dark kind of freedom. When I began to fight against it almost a year later, it was because I began to understand that life had moved on without me – sports, friends, boys, prom etc. I had wholeheartedly embraced nonexistence, only to find that nonexistence did not lead to societal acceptance, but to a lonely death.

“And so there I was where so many young woman were, trying to locate ourselves somewhere between being disdained or shut out for being unattractive and being menaced or resented for being attractive . . . trying to find some impossible balance of being desirable to those we desired and being safe from those we did not.”

“Disappearing Acts”

Most of the compliments about my thinness (and disparaging comments about other girls’ thickening, maturing bodies) came from a grade school friend who later came out as gay. I still remember him telling me that I was pretty “because you are skinny” and that other friends were losing their edge for “fat thighs,” “mom butt,” or “grandma butt.” He called my best friend a “butterface” (i.e. everything looks good but her face). I have no idea how he’d explain himself now, but I imagine that it was a way of processing his own sexuality; of coming to realize that he did not desire women’s bodies, and, taking full advantage of his power as a white male, used his voice to disparage and reject them. As Solnit says, within patriarchy “no [woman] is ever beautiful enough, and everyone is free to judge you.”

It’s a hard truth that in my own experience, the harshest judges were men who felt disempowered themselves – gay men, awkward men, short men, etc. Men whose fathers talked about women disparagingly inherited their menace. It all rained down on the teenage girls in my middle school and high school. And it shaped how we entered the adult world.

“There was a real joy in the creative and intellectual life, but also a withdrawal from all other reals of life. I was like an army that had retreated to its last citadel, which in my case was my mind.”

“Disappearing Acts”

Like Solnit, one of the only places I ever felt confident was in academia. Reading, writing, twirling ideas around my mind like a strand of hair around my index finger. If I am smart, so went my thinking, at least I have somewhere from which to draw courage. And writing was a place where I could say what I was thinking and feeling without fear of upsetting men — in other words, without fear of escalation.

Solnit’s greatest gift to me, and to all women, is finding the courage to become a writer (“despite it all”), and to hold fast to her perspective. She gives young women permission to question the literary and cultural canon, to investigate the untold impacts, and to push for change. She points out how many stories – told in books, on TV, in movie theaters, on podcasts, and in music feature the abuse, torture, and death of young women. Solnit observes this reality and its impact without agreeing that any of this (Tarantino, Eminem, The Ted Bundy Tapes) are productive, revolutionary, or attention-worthy works of art despite their commercial success. For me, that is a powerful permission to stand firm in my aversion to violent “art,” and to call it what it is: mundane.

In addition, Solnit gives herself (and everyone else), permission to put down canonical literary works that subjugate women, such as On the Road by Jack Kerouac:

“Diving into the Wreck”

“I did like some things bout Kerouac’s prose style, just not the gender politics of the three men who were most often meant when people talked about the Beats. . . It seemed to me that I would never be the footloose protagonist, that I was closer to the young Latina on the California farm who gets left behind, and halfway through I put the novel down. The book was going to go on without people like me, and I would go on without it.”

I’d recommend Recollections of My Nonexistence to any and every young woman, with the caveat that it’s not easy to read. But as Solnit herself says, “Sometimes when you are devastated you want not a reprieve but a mirror of your condition or a reminder that you are not alone in it.” Solnit reminds me of this, and makes my experiences, my painful memories, less personal. It’s not my fault that I was taught to be skinny and silent, and that I then became my own oppressor. It’s not my fault that my efforts to push back against the system that annihilates women — efforts such as not wearing makeup, not shaving my body hair, or not wearing a bra – actually exacerbate my fear and self-consciousness when I enter public spaces. It’s not your fault, either.

I’d also recommend it to men. As Solnit points out, “One of the convenient afflictions of power is a lack of [] imaginative extension. For many men it begins in early childhood, with almost exclusively being given stories with male protagonists.” She continues, “Perhaps there should be another term for never looking through the eyes of others, for something less conscious that even single-consciousness would convey.” I established that I have given permission to put down Kerouac (and DFW) thanks to Solnit. Still, I believe I am the better for knowing, intimately, the male reality — and for being taught (by default) to extend my perspective beyond myself.

It’s not always useful to spend a lot of time thinking about the things that make life hard or unfair. It can lead to despair. (In my case, it has to be followed by episodes of Parks and Rec.) What’s more — as Solnit emphasizes repeatedly, categories of doubly-oppressed women, such as young women of color, young women who are gay, or young women whose growing bodies otherwise deviate from Western beauty ideals, have whole additional systems working to exclude and disregard them. That’s a lot to face down, just to exist as a person every day. I don’t know what to do other than begin trying to take up space — even though it scares me.

For more on the treatment of women in Beat literature, read my earlier blog, “Watching Boys Do Stuff.” Thank you, Rebecca Solnit, for giving me permission to quit the Beats, and all woman-erasing literature put to page before or since. Not only giving me permission to quit, but giving me something encouraging to read instead.