2020 was a great year for reading, if little else. After Thom and I got married in Boise on February 22, we took a meandering road trip home and arrived in Indianapolis just in time to see a handful of friends before the threat of COVID-19 became clear. While sheltering in place, I tried to bang out a few extra blog posts, but mostly I consumed books.

Garbanzo doesn’t think much of War & Peace.

I made an effort to read more fiction this year, particularly new, popular fiction. I usually tend not to read fiction bestsellers unless friends specifically recommend them. I have found time and time again that these releases are overhyped and their popularity quickly flames out. (E.g., The Help, which was everywhere 10 years ago, is now considered regressive.) For me, Exciting Times, Sad Janet, Clap When You Land, A Woman Is No Man, and The Nickel Boys fell into this category for various reasons, all of which can be summed up as follows: they just weren’t that good. Allie Brosh’s new graphic memoir, Solutions and Other Problems also failed to live up to the standard set by its predecessor: Hyperbole and a Half. Still, in reading the “hot books” of the season, I did find a few gems. I loved August; Girl, Woman, Other; City of Girls; The Mothers; and Pachinko.

Memoirs continue to hold a special place in my heart and mind. This year, I read a few popular ones (Educated, Maid), and listened to others on audiobook. My favorite celebrity audiobooks this year were Born a Crime, I Have Something to Tell You, A Promised Land, and A Very Punchable Face.

The highlight in these last few months of 2020 for me has been reading the first 500 pages of War and Peace. (Right now I’m stalled out on p. 648, but plan to rev back up again soon.) I was driven to choosing a “classic” by irritation with several bad debut fiction reads in a row. Luster, followed by Exciting Times and Sad Janet were painfully self-conscious, and, it seemed to me, nihilistic and hopeless. I got to a point where I was like, “If I have to read ONE more book about a mid-20s woman who hates her job, has no money, and is having sex with a 40-year-old from the internet, I will lose my mind!” What is the point of this? Telling me that everything sucks? That is not what I’m looking for in a book!

So anyway, War and Peace it was. I was hungry for a moral vision of the world, hope, meaning found in suffering. It has been a topsy turvy year, and the chaos of the Napoleonic Wars has turned out to be as good a parallel as any. I am really enjoying Tolstoy’s broad insights about human life. For example:

“[Pierre] suffered from an unlucky faculty—common to many men, especially Russians—the faculty of seeing and believing in the possibility of good and truth, and at the same time seeing too clearly the evil and falsity of life to be capable of taking a serious part in it. Every sphere of activity was in his eyes connected with evil and deception. Whatever he tried to be, whatever he took up, evil and falsity drove him back again and cut him off from every field of energy. And meanwhile he had to live, he had to be occupied. It was too awful to lie under the burden of those insoluble problems of life, and he abandoned himself to the first distraction that offered, simply to forget them. He visited every possible society, drank a great deal, went in for buying pictures, building, and above all reading.”

Like Pierre, behind my reading habit is partly a need for distraction. Fortunately, reading happens to be a positive distraction for me (unlike, say, clothes shopping), but it is nonetheless something I turn to when I am world-weary. And this might be why I become particularly incensed with books that have a pessimistic view of humanity. (I’m trying to escape the bleakness, goddammit!) On the other hand, books that pique my curiosity, give me hope, and show me beauty can brighten my day and even transform my life.

I’ve blogged about a few of these already, but below I’ve marked in bold the books that have really stuck to my soul — the ones I’m still thinking about months after reading.

Fiction

- State of Grace – Joy Williams

- August – Callan Wink

- Exciting Times – Naoise Dolan

- Luster – Raven Leilani

- Sad Janet – Lucy Britsch

- Friends and Strangers – J. Courtney Sullivan

- Clap When You Land – Elizabeth Acevedo

- Girl, Woman, Other – Bernardine Evaristo

- The Vanishing Half – Brit Bennett

- Such a Fun Age – Kiley Reid

- A Woman Is No Man – Etaf Rum

- The Mothers – Brit Bennett

- The Nickel Boys – Colson Whitehead

- City of Girls – Elizabeth Gilbert

- Pachinko – Min Jin Lee

- The Most Fun We Ever Had – Claire Lombardo

- Women Talking – Miriam Toews

Memoir

- Solutions and Other Problems – Allie Brosh (Graphic Novel)

- The Spiral Staircase – Karen Armstrong

- Untamed – Glennon Doyle

- Recollections of My Nonexistence – Rebecca Solnit

- Educated – Tara Westover

- Maid – Stephanie Land

- Uncanny Valley – Anna Wiener

- This Boy’s Life – Tobias Wolff

- Coventry – Rachel Cusk

- Mental – Jaime Lowe

- In the Shelter – Padraig O Tuama

Nonfiction

- White Fragility – Robin DiAngelo

- Beyond the Gender Binary – Alok Vaid-Menon

- Last Days at Hot Slit – Andrea Dworkin

- Art and Fear – David Bayles

Audiobook

Memoir

- I Have Something To Tell You – Chasten Glezman Buttigieg

- A Very Punchable Face – Colin Jost

- Dreams from My Father – Barack Obama

- Born a Crime – Trevor Noah

- Carry On, Warrior – Glennon Doyle Melton

- Love Warrior – Glennon Doyle Melton

- A Love Letter Life – Jeremy & Audrey Roloff

Nonfiction

- Trust: America’s Best Chance – Pete Buttigieg

- Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now – Jaron Lanier

Unfinished/Stalled Out

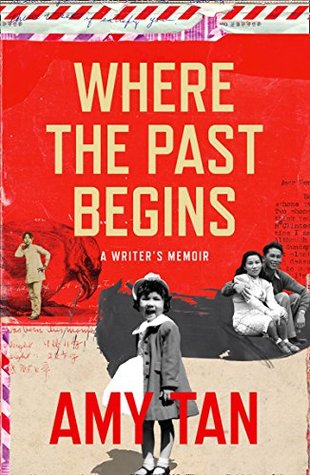

- Where The Past Begins – Amy Tan

- That All Shall Be Saved – David Bentley Hart

- The Evangelicals – Frances FitzGerald

- How to Do Nothing – Jenny Odell

- A Moveable Feast – Ernest Hemingway

In Progress

- A Promised Land – Barack Obama (Audiobook, Memoir)

- War and Peace – Leo Tolstoy