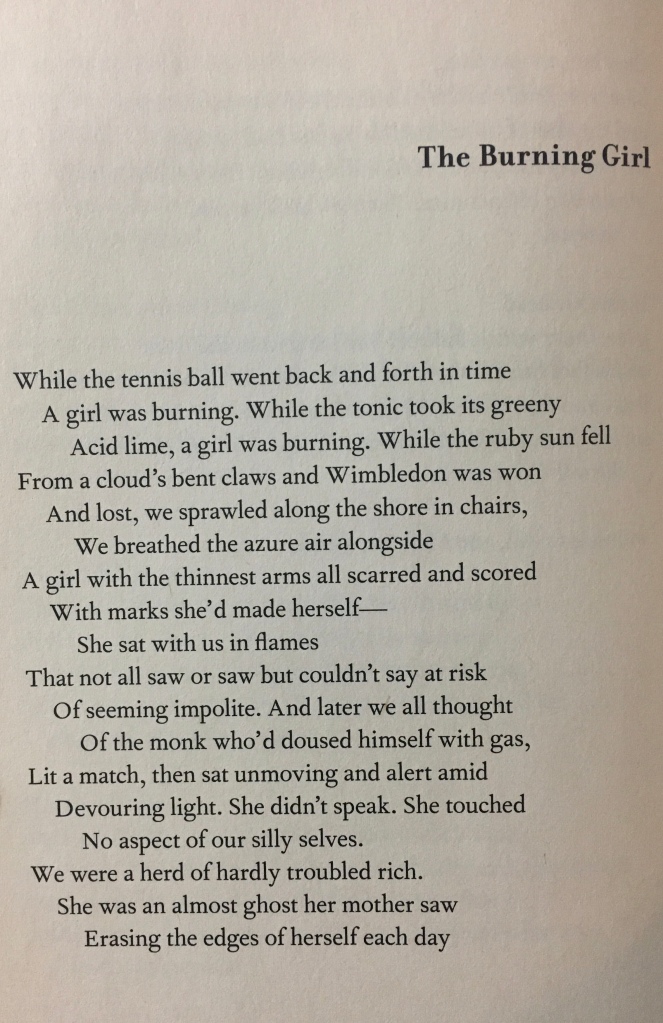

Mary Karr’s poem “The Burning Girl,” published in Poetry Magazine in May 2017 and later in her collection Tropic of Squalor (2018) is a devastating poem about a girl suffering from various self-harm disorders. While Karr attends Wimbledon with a group of friends, she observes her friend’s daughter as follows:

Listen to Karr read it herself here.

Karr’s “burning girl” is not the powerful “girl on fire” Alicia Keys sang of. (See here.) Nor is she the fully feeling girl Glennon Doyle describes in Untamed:

“The fire of pain won’t consume me. I can burn and burn and live. I can live on fire. I am fireproof.”

-Glennon Doyle, Untamed

Here, pain is a refining force, an agent of transformation. Its fire burns down old paradigms and allows the new, better, truer ones to grow.

Doyle understands her past addictions and illnesses as the product of pain avoidance. She writes:

“Pain is not tragic. Pain is magic. Suffering is tragic. Suffering is what happens when we avoid pain and consequently miss our becoming. That is what I can and must avoid: missing my own evolution because I am too afraid to surrender to the process. Having such little faith in myself that I numb or hide or consume my way out of my feelings again and again.”

-Glennon Doyle, Untamed

For Doyle, fire represents the uncomfortable feelings that come with being a human on earth — anger, sadness, resentment, hate, shame, etc. For nearly half of her life, she preemptively struck such feelings down with drugs, alcohol, binging and purging, etc. Letting herself become unguarded against these fiery feelings was how she healed.

But when I read Untamed last week, particularly the line: “I can burn and burn and live,” I was reminded of Karr’s poem. What of the real fear of getting trapped in the fire? How and why does that happen? What should we do about it?

“The Burning Girl” is not fireproof, she is tinder. Karr describes the girl’s arms as “birch twigs” and her body as a “flaming tower.” Even with “ocean endless” love from her mother, the girl’s flames are not extinguished, and ultimately, “she burned.” The past tense of this final line suggests that her body was consumed and she died. (So do interviews with Karr on this poem, in which she reflects upon the unimaginable pain of losing a child.) There is no resurrection, at least not here. The poet has witnessed the burning girl’s suffering in her last days, and that is all we have.

Karr compares the burning girl to “the monk who’d doused himself with gas, lit a match, then sat unmoving and alert amid devouring light.” Likewise, she reminds me of certain female Catholic saints and mystics who died of anorexia mirabilis, meaning “miraculously inspired loss of appetite.” For example, Saint Catherine of Siena died at 33 after she stopped eating anything other than the Eucharist. More recently, French mystic Simone Weil died at age 34 from self-starvation, allegedly out of solidarity with the soldiers fighting in World War II.

So, again, what about people like these – girls who get stuck in the fire? Who set themselves on fire in a misguided search for the Good? Can we learn to differentiate self-annihilating fires from the fires that enable us to become?

The primary distinction, as I see it, is that Doyle’s fireproof girl is in motion. She walks through and beyond the fire. She is alive. Karr’s burning girl, on the other hand, is stuck in it, unmoving: “She sat with us in flames.” Soon, she is dead.

We are fireproof in a human way, after all, bound by time and flesh. This limits our ability to withstand it. We need to jump in the ocean afterwards. Then maybe we need a long interval of watching Wimbledon in the 70 degree, partly-cloudy weather, tonic and lime in hand. In fact, I think this last in-between place is where we would be lucky to spend most of our time.

The essential mandate of motion during the fire walk reminds me of the “Beach Day” episode in Season 3 of The Office. Michael can’t even take the first step; Dwight overdoes it, falling on his stomach into the hot coals, insisting on staying down until Michael gives him the manager job; and Pam does the fire walk as designed, then is brave enough to tell Jim how she feels about him.

***

Why is it that so many of us stop walking and get stuck in our pain?

For some, myself included, a simple but important answer might be brain chemistry. For whatever reason, I am prone to getting stuck. To do the fire walk, I need a pair of thick socks, or else I turn into Dwight.

For a long time, journaling, running, music, etc. kind of did the trick to propel me forward when I hit the fire, but recently I’ve discovered how much better it is just to coat my brain in fire retardant ahead of time. Importantly, it’s not a pre-numbing; it’s an extra layer of padding. As my husband Thom observed, Prozac allows me to feel my fiery feelings but then later, feel better. Cry and then stop crying. Get up. Keep moving.

Doyle acknowledges her own need for additional padding, or fire-retardant. She writes in Untamed: “I am on Lexapro, and I believe it to be — along with the personal growth shit — the reason I don’t have to self-medicate with boxes of wine and Oreos anymore.”

I am with Doyle here. There are few things I am more thankful for than the invention of SSRIs.

My brain, left to its own devices has done a variety of weird things upon encountering fiery feelings. It has stopped all other activity and made it its full-time job to numb itself to the pain — reveling in its success. Like the burning girl. Other times, it has gone in the opposite direction and become hyper-feeling, so ceaselessly buffeted by pain that it becomes obsessed with it. In Darkness Visible, William Styron describes his depressed self as follows: “My brain, in thrall to its outlaw hormones, had become less an organ of thought than an instrument registering, minute by minute, varying degrees of its own suffering.”

Thus, in my experience, feeling too intensely can be just as confusing and destructive as becoming numb. I’ve tried to ditch pain — too cool for it — and I’ve also tried to get an A+ in pain. It’s as if my subconscious wants to outsmart all oncoming fires by beating them their natural conclusion. Meanwhile, this need to direct and control the fire only amplifies its importance; making its effect way worse than it was ever going to be.

Karr’s burning girl continues to haunt me. She’s dead and gone, not saved by the vast love shown her the poem. “She burned,” and there is no certainty of resurrection. Perhaps all we can do is bear witness — which is what Karr does. “Force her sadness close,” she writes. It seems insufficient. In moments like this, I turn to T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets — that perfect meditation on human insignificance, temporality, and the circular nature of all things. Any excerpt might do, but here’s a favorite of mine:

I loved this essay. I loved the Karr poem at the top, which i’d never resd. I loved all the twists and turns in the essay and the easy, natural transitions to Glennon Doyle, St. Catherine of Siena, The Office, prozac, and even TS Eliot. That’s a lot of ground to cover, but it all felt natural and organic. I’ve always been particularly interested in that monk who self-imolated in 1963. There’s a haunting video of the act on YouTube, set to spooky etherea music by a Russian band called Mooncake. One of the fascinating things is to watch the evolving reactions of the hundreds of monks and soldiers who are witnessing the act. I’ll link below. Not for faint of heart, of course. But it was yet one more crazy thing which happened in 1963 (just 3 weeks before JFK killing) and was floating around in the collective consciousness of the 1960s.

I loved your observations on consuming fire v. purifying fire. Another really beautiful and brave essay. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person